When this question was posed by Larry Ferlazzo for his column in Education Week, we were happy to respond with our strategy to engage students by encouraging them to see every piece of writing as an evolving document. (see below). He received four strong responses and we urge you to read the full context of the article here. You will find our writing and revision strategy in practice in the RWS lessons as we guide students to first sketch their writing in a Version 1 and then flesh out that simple beginning by adding detail and complexity. For a deeper dive into our writing process, you may wish to review our book From Striving to Thriving Writers, Strategies to Jump-Start Writing. (Scholastic)

Sara Holbrook is a novelist, poet, and educator with a multitude of books for both teachers and students under her belt, including The Enemy: Detroit, 1954, which won the 2018 Jane Addams Children’s Book Award.

Michael Salinger is a poet, performer, and advocate of poetry and performance in education.

Together, they co-founded and direct Outspoken Literacy Consulting, an organization that runs programs to help K–12 students in the United States and around the world develop writing, public speaking, and comprehension strategies:

We begin very simply and then increase complexity with subsequent revisions. A writing lesson might go like this:

- Think of a simile comparison regarding XYZ. (This is Version 1.)

- Use that to develop a more complete description of your subject matter. (This is Version 2.)

- Can you add some sensory terms to bring the reader into the scene? (This is Version 3.)

- Bring a character into the situation. What would that character say? (This is Version 4.)

How did we come up with this approach? This is how we write. We are both trade book authors and writers of professional development books. Before that, we were both business writers—Michael was an engineer for 23 years and Sara was in public relations. We deconstructed our writing practice and realized a couple important things:

- We never start at the beginning of a long piece of writing, develop a story arc according to some predetermined pattern, and then use a rubric to make it right.

- All writing is creative. Any time we begin with a blank page and put words on it, it is a creative process.

When we visit schools, we show teachers how they can use simple frameworks to help students jump start their writing by starting with Version 1. We show them how we guide students through the next couple versions. Writers will discard the framework as the writing takes off on its own, kind of like taking off the jumper cables after the car is running.

Kids intuitively get it. We compare the writing process to playing a video game or learning a sport; people start with simple moves and level up. Students begin to internalize the reality that revision is incremental and writing is always an evolving process. We’ve found that the teachers we work with are excited by this writing process, and even relieved. Start simple and add complexity is a recipe for success as students adopt an “I can do that,” attitude.

We actually have kids bragging,

“I’m on Version 6!”

But one of our favorite lines to hear from kids is, “Oh, don’t worry, just put it down. It’s only Version 1.” We reinforce that no one expects the first version to be perfect, it’s just something to build on. And then we offer choices on how to take that next step.

We also invite students to share aloud throughout the writing process. By reading aloud, Version 1 and Version 2, partnering, or working with a mini writers’ group, students are able to see and hear their own progress as writers. We’ll ask, “Which version is working better for you?” Then we’ll let the writer explain what made the revised version better and where they want to take it next.

By building revision into the beginning of the writing process rather than leaving it until end, students are eager to add complexity and clarity to their writing.

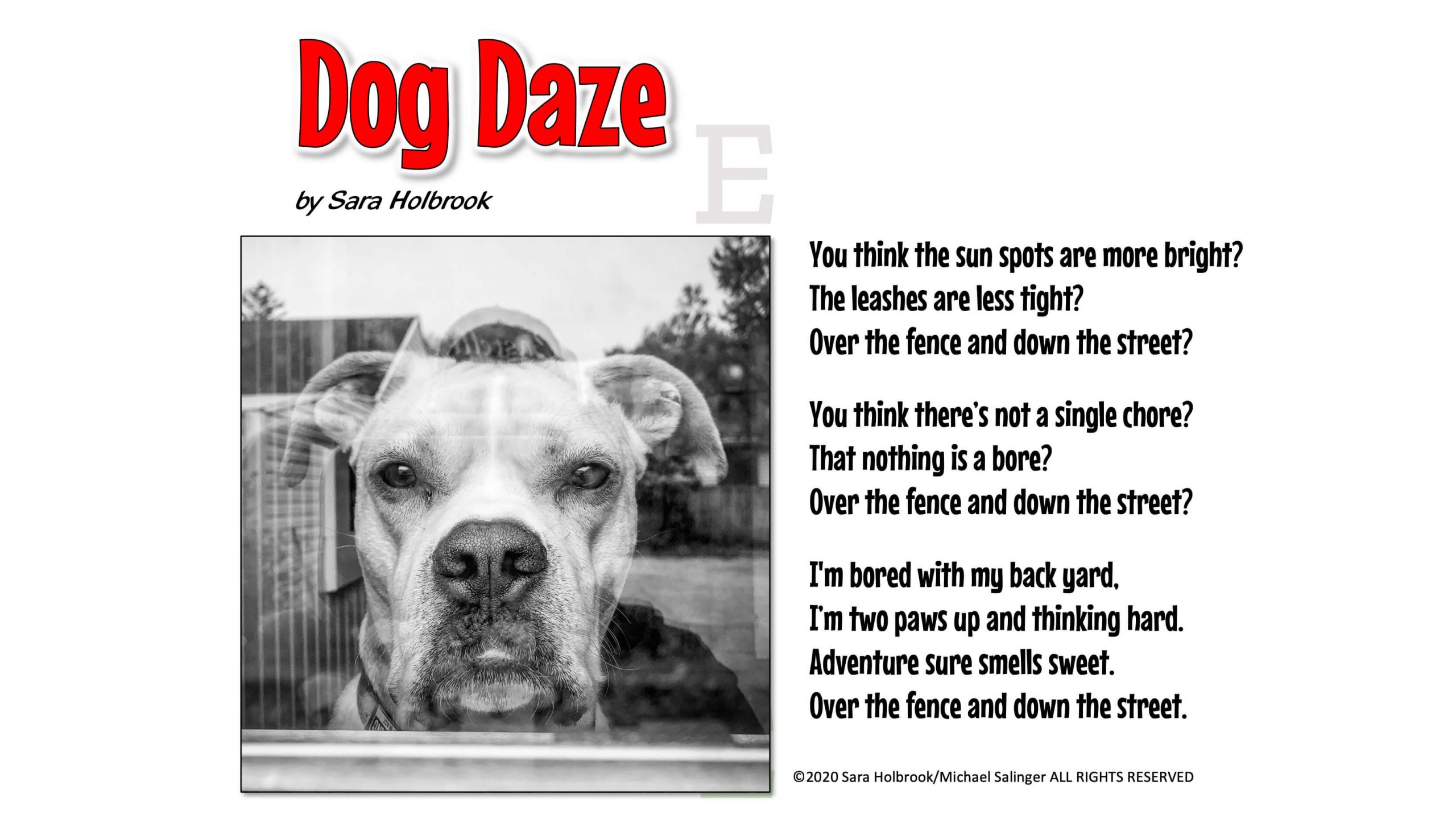

Below find an example of a quick write slide using a Version 1.